In my excitement about tiny shrimp, I’ve neglected some older sets of photos. In this case, some photos of birds that I took while surveying for sea turtle tracks on the beaches at Baie de Grandes Cayes and Baie de Petites Cayes. The photos start on the beach at Grandes Cayes with semipalmated sandpipers hopping along the sargassum floating just off shore. After a few other feeding shorebirds are featured as well. Progressing north to Eastern Point, we see on of my favorite birds on the island, the American kestrel, known locally as the killy-killy. These can often be seen in this area, usually perched on the rocks looking across the low grass field for food. The set ends near Petites Cayes with another favorite, the American oystercatcher. This bird typically travels in couples, but the one we often see up there is always alone.

After figuring out how to find the critters hiding in the sargassum, I couldn’t help but do the same thing again the next day. I didn’t really change my technique, but I figured I would post Sargassum II: Crustacean Bugaloo anyways.

If you’re curious about the technique for photographing them, it was pretty simple. I used a coffee filter to strain the sea water so it was relatively clear and put it into a clear glass bowl with a little flash on each side, triggered by my camera. To get underwater, I just used the flat port from my camera housing, holding it in the water with one hand while I pointed the camera with the other. I think a better approach would be to use translucent container (like tupperware) that would act as a diffuser and put a matte-finish bottom inside the container maybe either black or white. Perhaps I can try this next time.

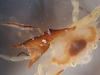

Below are a whole mess of photos of shrimp and crabs. One thing you might notice on many of the shrimp is a lump on one side of the thorax. These are isopods which parasitize the shrimp. Specifically, they are from suborder Epicaridae, which includes a variety of isopods that parasitize crustaceans (or actually, other crustaceans, because isopods themselves are also crustaceans). The females, which are much larger than the males, attach themselves to the gills of their shrimp hosts and feed on their blood. Often, and it looks to be that case in these photos, the shrimp actually grow their carapace over the isopod, creating the lumps you see in the photos (compared to the symothoid isopods you can see on fish, where the isopod itself is visible). Also, there was one free-swimming isopod that you can see below, it’s dark and curved.

When the wind changed directions yesterday, it brought to Grand Case the sargassum that has been amassing on St. Martin’s eastern shores for several weeks. In the North Atlantic’s Sargasso Sea, this algae provides shelter for a variety of organisms, such as juvenile fish and invertebrates. So, even though the bay was rough and cloudy, we went out to investigate the floating patches of sargassum.

I found it was possible to find some shrimp amongst the sargassum, although it was tough to do while snorkeling. Instead, I developed another approach, grabbing clumps of sargassum and shaking them out over a plastic bowl. Using this method I was able to to find a variety of creatures, mostly shrimp of different sizes and colors. I also found a few small crabs, including one very strange looking larval crab.

Did they really come all the way from the Sargasso Sea? I’m sure some of the critters could have joined the floating caravan as it has travelled this way, but I would guess many or most of them are, like the sargassum, far from their normal home. Apparently there are a variety of shrimp from the genus Latreutes and others that are residents of the sargassum, often adapted in color and shape to be well camouflaged in that environment.

What is their fate? It would seem that they’re mostly doomed as their homes wash up on the beach. Even if they manage to stay in or get back to the water after their sargassum is gone they would make an easy meal with no place to hide. In the meantime, anyone with a bucket and a little patience can explore an ecosystem that’s traveled hundreds of miles to visit our island.

Below are some photos of crustaceans taken from sargassum, mostly a variety of shrimp. If you look closely, you can see eggs on the underside of some of the shrimp, and organs through their transparent shells.

I recently finished watching the lectures from Sean Anderson’s Conservation Biology class on iTunes U. Compared to the last course I watched, Principles of Evolution, Ecology and Behavior, Conservation Biology is less revelatory and perhaps less interesting for a layperson, but that’s not a criticism of the course itself. Conservation Biology has a much narrower focus, which inevitably means it will have a narrower audience.

What you do get is pretty great for anyone interested in the subject. On the scientific side, concepts like island biogeography and metapopulations are covered in detail. There are also many discussions of conservation history and policy, so you end up with a good understanding of topics like the history of protected areas and the Endangered Species Act. This history helps put the current conservation thought and policy in context. There are also a number of lectures which illustrate conservation principles by focusing on a single species, which are quite excellent.

Overall, I really enjoyed this course. I would highly recommend it to anyone interested in the topic. Anyone more interested in an introduction to big ideas in science would probably find this class a little too detailed. On a practical note, the lectures aren’t numbered in iTunes and there are lectures from multiple years available. I watched the 2011 series, and a few of them appear out of sequence in iTunes, but this wasn’t an obstacle to understanding or enjoying the lectures.

The northeast portion of St. Martin is a hilly lobe, separated from the central mountains by a lowland area stretching between Grand Case and French Cul-de-Sac. If the water level were a little higher, the sea would run from Grand Case through the airport and Étang Chevrise creating a little island. On the eastern side, there’s the wilderness area that wraps around from the dump to Anse Marcel, featuring the longest stretch of undeveloped coastline on the island. The interior of that area is also mostly undeveloped, although Cul-de-Sac is expanding in that direction.

Moving westward, the majority of the area is undeveloped, but used as pasture for goats and cattle. The most heavily grazed areas are fields of stones and ankle-high grass with very little wildlife. Other areas are more of a scrubland with taller grass and shrubs. Some of the hilltops are forested, particularly the hills leading out to Bell Point. It can be interesting to see the stark differences in the landscape when crossing through this area, each fence marking a transition from pasture to scrub to forest and back again.

A look at older photos shows that there is actually considerably more vegetation here now than there was fifty or one hundred years ago. The shift in the local economy from agriculture to tourism has presumably reduced the amount of land used for livestock, and development has yet to move past the lower reaches of these hills. I wonder what this area will look like in another ten, twenty or fifty years. Perhaps most of the livestock will be gone and forested areas will expand down from the hilltops, while new housing extends up from the roads, a future that is both better and worse than the present.

Below are a few photos from this area, although most of them are from the airport pond and road area.

By now St. Martiners are plenty familiar with the huge influx of sargassum that has washed up on our eastern shores. You may have also noticed how abundant shorebirds and other birds are on those same beaches right now. Is there a connection and perhaps a silver lining to this smelly nuisance?

The starting point for a possible connection is the impact of the sargassum on invertebrates that scavenge vegetation on our beaches. Although I can’t be sure, it seems highly likely that isopods, insects and other small, coastal detritivores are experiencing a population explosion due to the large increase in available food and shelter. Shorebirds are obviously foraging on these mounds of rotting algae, and other birds like the barn swallow are feasting on flying insects in these areas. But are we seeing more birds right now? If so, how could that be?

Probably the total bird population has not increased. After all, unlike insects, most of these birds only breed once a year, so it is too early to see much of an impact in overall bird numbers. It’s possible that some birds that might have starved in a normal year would have survived with this extra food available, but that’s probably a relatively small number.

On the other hand, we are in the middle of a pretty busy time for migration, with many species either arriving to or leaving the island between August and October. Perhaps it is possible that some birds would stay here a little longer than they otherwise would, increasing the local population. Presumably the extra food wouldn’t encourage birds to fly here earlier than usual, because they would have no idea that the extra food is here. I think it is possible that if some birds delay their annual departure and others take longer visits as they fly over, this could be noticeable, particularly when combined with the normal seasonal arrival of other species.

Another possibility, which seems pretty likely and may be happening at the same time, is that bird populations on the island have gravitated towards the impacted eastern beaches to take advantage of the resources there. In this case, people (like me) may be more apt to notice the large numbers of birds on some beaches while not noticing that other areas have fewer birds than normal.

Of course, maybe nothing special is happening at all. Shorebirds arrive on the island at this time of year every year, and unless you’re counting, it’s hard to tell if there’s really any difference this year. Unless someone is actually studying this on one of the affected islands, we probably won’t know. It’s too bad school is out for the summer, because this would be a pretty great science fair project.

Below are some photos from Baie de l’Embouchure. Right now you can go there and see a lot of sargassum and lots of shorebirds.

Above is a photo of a ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres) that I took yesterday at Salines d’Orient. When reviewing my photos in the evening, I noticed it has a flag on its left leg that says PU6. Although it hadn’t occurred to me before, in retrospect it seems obvious that there is at least the potential to see banded birds on St. Martin.

If you live on the island or have visited at different times of year, you’ve probably noticed there are a number of birds that are only here part of the time. The laughing gull is probably one of the most noticeable, but maybe you’ve also noticed that the population of barn swallows on the island has gone from none to roughly a bajillion in the last week or so. St. Martin is a temporary home for many migrating birds that spend the rest of their time in North or South America. I would go so far as to guess that the majority of species that can be seen on the island are migrants.

This turnstone was banded in the US, probably on the Delaware Bay, which is a major stopover point for this species. Adam from EPIC says that he sees banded birds here, particularly ruddy turnstones, on a regular basis. I found a couple places to report banded bird resightings: bandedbirds.org and reportband.gov.

Reporting banded birds is an easy way to get involved in research and protection efforts, and adds some extra excitement to birdwatching. On bandedbirds.org, you can find information about what species are banded and what information to record when you see a banded bird. Obviously, the bands and rings used to identify the bird are important, but it is also valuable to record information about things like the number of birds in the flock and the ratio of banded to unbanded birds.

Saint Martin is just one small island, but seeing banded birds is a reminder that the fate of ponds, wetlands and coastlines here has an impact on animals that live as far away as Canada and Brazil. Good luck spotting some banded birds!

For a number of years, the ongoing spread of invasive lionfish in the Atlantic and Caribbean has been the hottest story in marine biology. The invasion has been unprecedented in its speed and impact, from one or more initial introductions probably in the early 1990s to their increasing range and ballooning populations today. Today, they can be found along the east coast of the US from North Carolina to Florida and in most of the Caribbean. In the future, that range may extend to the southern end of the Brazilian coastline.

As the problem has progressed, our ideas about how to address it have changed as well. However, it seems like the lionfish invasion is not only outpacing our efforts to control it, but also our thinking about the problem. As far back as 2003, the NOAA issued a report conceding that elimination of the lionfish was “nearly impossible.” Even back then it occupied much of the southeast US coast, in a wide variety of habitats and in surprisingly high numbers. Still, we held out hope that we could keep it from spreading or manage the population. As it reached each new area, we headed out with nets and spearguns hoping to keep it from becoming established only to fail every time.

To take a step back, humans don’t have a great track record of eradicating invasive species. I think we’ve done it a few times, mostly eradicating goats or rats on uninhabited islands with great effort and expense. The lionfish problem is many orders of magnitude greater. They reproduce quickly and can travel unrestricted throughout the Atlantic and Caribbean. Like many tropical fish, during their larval stage, they are thought to ride the open ocean currents for weeks before settling down. Only a small part of their habitat, shallow reefs visited by snorkelers and divers, is even accessible to humans. At best, eradication could only happen in the tiny sliver of habitat where humans are present and would easily be re-invaded by individuals from the next island or even just a few hundred meters away in deeper water.

To be fair, a typical lionfish plan also includes studying their impact on local ecosystems and raising awareness in the local population. These two goals are worthwhile, and they implicitly assume that lionfish are here to stay. Annual lionfish hunts and the recent push to drive interest in eating lionfish, on the other hand, get much more attention in the press and the public imagination. Biological control, such as attempts to “teach” grouper to eat lionfish are more plausible than going out to catch them all by hand, but at best would only adjust the eventual population equilibrium they reach.

Of course, I would love it if we could eradicate lionfish in the area, and I think it is admirable to give it a shot. At the same time, it seems pretty clear that it won’t work. I think that’s pretty hard to admit, but consensus is bound to move that direction. As we move in that way, the main question will be, how do we preserve marine ecosystems as best we can despite the presence of lionfish?

That’s a harder question to answer. More robust marine ecosystems will probably fare better, so expanding marine protected areas might help offset losses due to lionfish predation. Artificial reefs could increase the total available habitat for reef fish as well. Because small and juvenile fish are particularly vulnerable to lionfish predation, it may be worthwhile to create protected nursery areas. If I were more knowledgeable, I would probably have more or better ideas, but I’m sure those will come as the focus shifts from attempting to control lionfish to doing what we can to save the rest of the ecosystem. It won’t be easy, but at least it won’t be impossible.

Below are some photos taken while snorkeling in Grand Case Bay. There’s a lionfish in the piece of pipe, and the photo after that shows a lionfish marker placed at the site, which is used to make it easier for the marine reserve to find and capture the lionfish. Many of the other photos feature juvenile fish that don’t yet know how threatened they are.

Lately it seems like there is always another tropical storm just over the horizon, threatening us with death and destruction. Setting aside for a moment the impact on people and property, let’s consider the impact on wildlife on the island.

It’s been over fifteen years since the last major hurricane hit St. Martin, and according to many folks who have been around here since then there is a lot more wildlife on the island now. The bananaquit (Coereba flaveola, also known as the sugarbird or sucrière), which is extremely common on the island today, was rarely seen in the years after Hurricane Luis. Surely the same is true for many other species that are not as noticeable or well-known.

Even though hurricanes are a natural phenomenon that has impacted the Lesser Antilles since long before the arrival of people, habitat destruction has increased their impact on wildlife. Species that may already be struggling to survive in limited, degraded habitats may by wiped out entirely by a hurricane or take much more time to recover. Differing rates of recovery between species could alter the balance of our island’s ecosystem either temporarily or permanently.

A major hurricane is, in some ways, a big biological experiment. It has the potential to reveal a lot about how island ecosystems are impacted by a natural disaster and how they recover. Of course, much of what we could potentially learn is limited by what we already know about the island in its pre-hurricane state. In many ways, we don’t know that much. For example, there are several species of dove (zenaida, Eurasian collared and white-winged) that are similar in size and preferred habitat and probably compete with each other. If we don’t have a good idea of their relative populations today, we won’t really be able to tell if that changes after a hurricane.

On the other hand, even without a great deal of systematically-collected data, we would probably learn more about the impact of a major hurricane than we did last time around. In addition to data collected by the Réserve Naturelle, the Nature Foundation and groups like Environmental Protection in the Caribbean, there are plenty of less formal sources of data. Digital photography and online photo sharing, for example, will give us a much clearer visual picture of the impact of a hurricane next time around. With more dive centers on the island, there are more people familiar with the local marine environment than ever before. Hiking clubs, like St. Martin Trails, not only increase the number of people with firsthand knowledge of the island, but also make it easier to contact those people to collect personal observations.

Overall, the next big hurricane will be something of a missed opportunity to seriously study the biological impact of such a disaster. On the other hand, we’ll surely learn a lot more than we have in the past, so at least that’s a start.

I’d love to know more about the history of Terres Basses, the lowlands area to the west of the Simpson Bay Lagoon. From what I can gather, it was mostly uninhabited and unused until the mid-1950s, when most of it was bought by an investor from the US Virgin Islands. One gentleman I spoke with recalled the area from his childhood, when his father was helping to build some of the first villas in the area. He mentioned that there used to be a sand road through the area that was at times entirely covered with red crabs. Apparently workers from Guadeloupe who had come up to do construction were amazed that St. Martiners didn’t eat the crabs.

Because the area is relatively flat and dry, it was probably of little agricultural value, leaving little incentive to make the area accessible. Apparently the first real road was built privately, starting in 1963, turned over to the government in 1968 and only paved in 1975. As fascinating as it would be to know the history of the area before the first tourist development, perhaps there wasn’t much history there to speak of.

Below are a few photos of animals seen on a recent visit to Terres Basses. Because the area is somewhat separated from the rest of Saint Martin, it could potentially host some species that are not found, or rarely found, on the rest of the island. The spider with the green abdomen (probably some kind of Eustala), for example, I have seen only in that area. It was also interesting to find two tetrio sphinx caterpillars that were not on frangipani plants, which is their normal larval host.