EPIC has been banding songbirds for about twelve years on St. Martin, making it a pretty unique long-term study for the Eastern Caribbean. The birds they study are primarily songbirds, and they include both year-round residents and winter migrants. The banding took place at Loterie Farm, at a stream flowing down the slope of Pic Paradis.

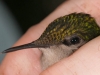

Each year, mist nets are placed in the same locations, and the data about captured birds includes weight, measurements, sex, age, presence of parasites and fat and muscle accumulation. Migrating birds, for example, accumulate fat and muscle before migration which is depleted over the course of migration. For local birds, size measurements can point to small differences in bird populations on different islands, or help establish the basic morphology of birds that have not been studied extensively.

Banding the birds can help establish migratory routes when the birds are recaptured either in the Caribbean or in their summer homes in North America. It can also give clues about the habits of birds, for example, catching the same bird in the exact same spot can indicate that birds maintain a very specific territory.

A long-term study, like this one, can also show patterns year-to-year or over longer periods of time that can illustrate the impacts of weather or the overall health of the ecosystem. This year, for example, water is very abundant in the survey area, which greatly reduced the number of birds captured. In a dry year, the nets are located at one of the few local sources of water. This year, with water everywhere, far fewer birds were visiting this particular stream.

On the first day I was there, I was able to help set up the nets, and Adam from EPIC explained the capture and data collection process. With few birds captured, only a single Antillean crested hummingbird while I was there, I also had some time to scout the forest for some interesting invertebrates, including a large katydid nymph, some tiny barklice and a variety of flies.

On my next day of banding, captures included a bananaquit (local) and an American redstart (migratory). Once again, there was plenty of time to look for interesting creatures in the forest and I found some beautiful green jumping spiders and a very well-camoflauged spider eating a caterpillar.